This is a repost of an essay I wrote almost ten years ago. I was struggling to articulate some of these ideas this morning, and in the midst of my discouragement, looked up this essay for reference and realised it said everything I wanted to. Times have changed, I have more children to eat up those quiet moments, but the realisation at heart of this writing continues to bear such rich, quiet fruit in my life. I can see God leading me in the paths of quiet, of homecoming, of love, of his grace over many years and I decided to share the history of that journey here today.

Lent is the season in which I rediscover love.

But when I first began to attempt the ‘practise’ of Lent, I mostly equated Lent with law. With repentance, yes, and under grace, I know. After all, Lent ends with Easter and a feast to mark salvation. But since discovering this season of the church, I’ve often seen ‘the penitential season’ as a time in which I made laws of discipline to express my true contrition, to prove to God that my sorrow over all the ways I sin and fail is real.

Lent dawned bright this year in England, bright as my good intentions. On the day when much of the church begins a season of repentance, the sun blinked and gleamed in a stark blue sky and birds whistled as if it were May and the daffodils in the vase on my desk finally bloomed.

But that evening, after a long day, after a service in which the ashes of repentance were crossed into my forehead and those of my children, I looked down the long trail of the coming days, and all I saw was grey. I was weary and afraid, doubtful that I could keep strict laws or great fasts. Part of me so yearned for spiritual renewal that I felt willing to attempt a great effort in order to gain a deeper sense of spiritual life. But my body, my heart felt too busy and sleep-deprived to keep up the strictures of dawn devotion or the renunciation of chocolate. (You know?)

So my Lent began as it often has, in doubt - of myself, and let us be honest, of God’s capacity to love an undisciplined me. I might have spent the whole of this quiet season in just such a mindset was it not for an encounter with a passage from Luke (during one of those attempted dawn devotions) and a woman of whom a self-righteous pharisee named Simon spoke exactly the words I felt were true of myself: ‘she is a sinner’.

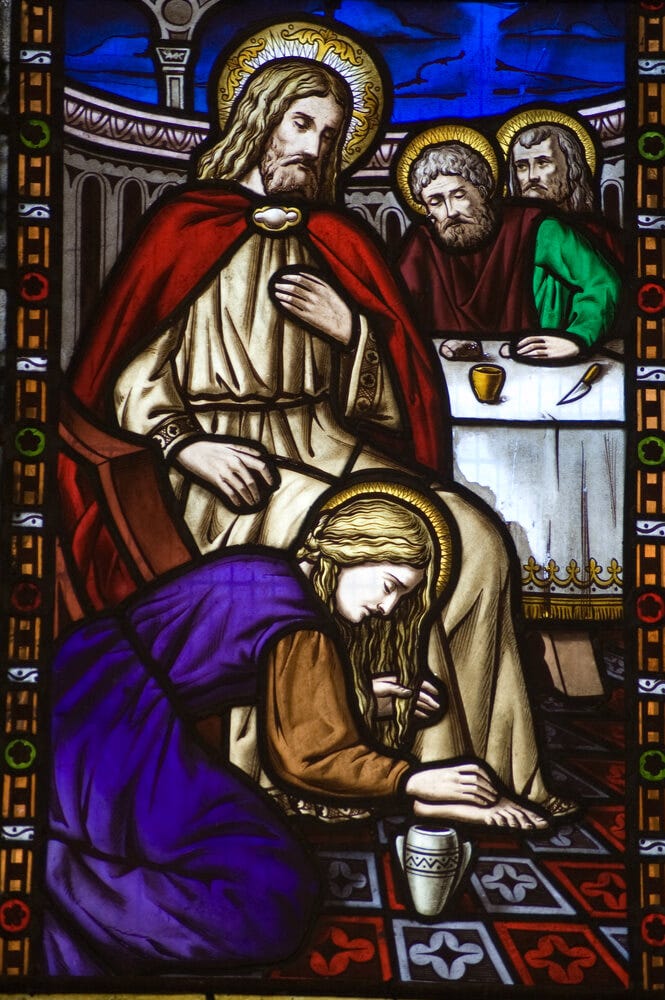

The story in Luke is set in the pharisee’s home at a dinner held for Jesus, ostensibly in Christ’s honour, but presumably to prod and test him, find out if Jesus was, by pharisee standards, 'the real thing'. Simon comes to his own conclusions when a woman who had ‘lived a sinful life’ creeps in to express her love for Jesus. Bringing an alabaster jar of perfume and a heart so brimful of repentance that it spills into tears, she kneels at Jesus’ feet to weep and wash him with her tears.

Simon’s conclusion is instant. If Jesus really had God in or with him, he would know what kind of sinful woman was touching him. (And, Simon must have assumed, send her packing.) For Simon was one of the pharisees who counted out tithes even of their mint leaves, kept the minutest tenets of the Law, tithed and cleansed and followed the Law so well that even God, they thought, couldn't condemn them. But Simon was also of those, according to the passage just before, 'who rejected God's purpose for himself'. And what was that purpose?

Love.

For the marvel of the story is that Jesus knew exactly what kind of woman was bathing his feet with her tears. He knew exactly the sin and grief that tortured her heart. He also knew the elaborate facade of good deeds and correct opinions by which Simon, the supposedly spiritual leader, kept guilt at bay. So Jesus told a story of two debtors, one who owed much and one who owed little. Both are forgiven by a generous moneylender and at the conclusion, Jesus simply asks of Simon which of them will love him more?

'The one who was forgiven most', says Simon, of course.

'Like this woman at my feet', says Jesus, 'who has loved and wept and washed me with her tears, while you have not even given me the kiss of hospitality or a towel to wipe my weary feet. She has been forgiven much, and so she loves much. But he who has forgiven little, loves little.'

In a brief stab of insight I saw myself both in Simon and the woman. In Simon, because with him, I thought that God’s acceptance of me dwelt in my being correct and keeping my countless little laws of performance. Because after all these years of wrestling and beauty and grace, I still sometimes try to reach God by the stretch of my own aching effort. In the woman, because deep down I knew myself frail and weak, unable to assure my own salvation or a five-minute quiet time, or even abstention from chocolate for forty days. Both were equally sinful, but one hid it even from himself, and so did not recognise Love at his table, while the other in her repentance saw him clearly and wept with gratitude.

In that moment, my understanding of what it means to keep Lent changed. Lent often has the reputation of being something that the super godly do, a sort of iron man competition. I think we often look at the spiritual life in general this way. I look at the people near me in study and church and think that everyone must be doing it better than me as I scurry through papers and strive to make time for those I love and try to catch sleep and make it to my kitchen at night too tired to cook, let alone pray. The irony is that Lent (not to mention the Gospel) is precisely for the lost and discouraged, the brokenhearted and disappointed who know they have nothing left to give. Lent is for the hurried and distracted, the lonely.

The disciplines of Lent - prayer, devotion, fasting, stillness - aren’t meant as a heightened performance, an extra extravagance of discipline to prove we’re really Christians. Rather, they are meant to create a quiet space in which we listen afresh for love, ‘accept God’s will’ as we come and remember that we are forgiven. Discipline is a good thing - quiet is a gift. But only if rooted in Love and used as a means to push back the cacophony of life long enough for us to look heartward, knowing ourselves afresh as the ‘sinful women’ and ‘wretched men’ in whom God’s plan to save the world by grace is worked.

But we find that grace only when we face what needs forgiving. As long as we, with Simon and the pharisees, believe we need not repent, need not admit our insufficiency, we will simply stand rotting and wounded in the armour of our good deeds and defiant self-confidence, dying, if we only knew it, of the festered guilt we will not face. In facing that messy guilt, in coming to the broken place in which there is no longer any scaffolding of piety to uphold us, any pretense of righteousness to disguise us, we discover, first, our eternal inadequacy. And second, grace. Real grace. Not the cheap kind that slaps a mask over a distorted face, but the deep kind, the backward working magic of Christ in which we are met in our most broken places by Love.

I changed my Lenten rhythms after reading that marvellous story. I haven't managed the giving up of chocolate or the eager rising at dawn each day that I desire. But I have stepped away from certain distractions, including the great one of self-loathing, and taken the extra quiet to listen, to pray. I’m treasuring my times to journal, just to keep my soul in the habit of articulation, and in the posture, once again, of listening. I've read a couple of novels whose words drip with grace. And in the hushed moments of these sweet times, I remember that I am forgiven.

And ah, how much I'm learning to love.

I'd love to know which novels drip with grace for you! Would you be willing to share a list? I'd love to read one during this time.

This was so beautiful, Sarah! I have been struggling a great deal with thinking about Lent, fighting to fast and pray because I started to think it was what I had to do to prove my love for God. But your words opened my eyes to the reality of the season; that it is not about my love for Him, but about His love for me, and my resting in that.

I especially loved this part of the essay: "The disciplines of Lent - prayer, devotion, fasting, stillness - aren’t meant as a heightened performance, an extra extravagance of discipline to prove we’re really Christians. Rather, they are meant to create a quiet space in which we listen afresh for love, ‘accept God’s will’ as we come and remember that we are forgiven."

Thank you so much! I did not know how I much I needed to hear this until I started reading. These are words that I will come back to ten million times as we journey towards Easter.